Introducing our Building Block

Building a business takes extraordinary hard work, resilience, judgement, intellect and luck. Fortunately, we are going to bypass all of this in the next five minutes as we cheat and build a business using a simple financial building block. The only attribute you will need is a bit of patience as I try to explain!

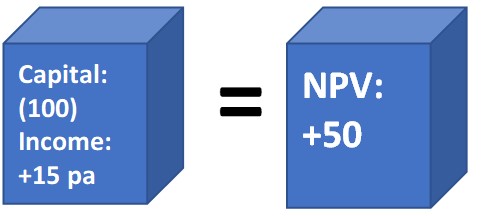

Figure one illustrates our basic building block. It represents our business’s annual operating cycle investing £100 of its retained capital into new projects and reaping a reward equivalent £15 each and every year after that. The business is able to create a new block every year and for our purposes, we will ignore things like inflation, replacement costs, or whether this steady state has a horizon at which returns fall away. Two critical inputs determine the value of these building blocks and therefore the business:

1. Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is the rate of return that the businesses owners demand

2. Return on Capital (RoC) is the rate of return the business derives from the assets it buys or creates.

Figure 1: the basic building block of our business

Figure 1 shows that the building block generates a RoC of 15% (15/100).

The Past

Let us suppose that the business has been able to put 20 building blocks together in the past. Invested capital therefore would have been £2,000 but remember this is now a sunk cost. This capital exists on the balance sheet and accountants still think its relevant as they depreciate it, but in reality for the purposes of valuation it can be ignored. What is relevant however is the £300 (£15 x 20 building blocks) of annual cash flow generated today and every year stretching into the future from these historic investment decisions. In terms of valuation we are fortunate that our business is traded on the stock market.

Figure 2: trading our business on the stock market produces a measurable Cost of Equity

Figure two shows that the stock market facilitates the derivation of a Cost of Equity for the business, determined from the βeta of the share price and the CAPM equation[1]. Cost of Equity is of course still available for untraded shares through comparison with similar listed businesses. Let us assume that Cost of Equity is 10% for our business and using another simplifying assumption, no debt, this gives us a WACC of 10%.

What is our current cash flow of £300 worth using a WACC of 10%?

Part one of Our Valuation: the current annual recurring cash flow of £300 is worth £3,000[2] (£300 / 10%)

The Future

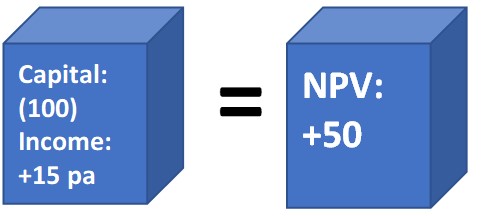

Our business will add one more building block every year. Figure three explains how the components of the block, the capital invested and the annual recurring cash flow, are actually worth exactly the same as £50 in cash today: you would happily buy or sell a building block for £50 cash.

This simplifying step means that the future value of these blocks is actually the same as a string of cash flows of £50 stretching into the future and starting in one year’s time.

Part two of Our Valuation: the future recurring cash flows of £50 is worth £500 (£50 / 10%)

Figure 3: Our building block is worth a cash equivalent of £50

We should however add another step in determining the future value we have just arrived at above. We need to consider that the business is generating £300 of cash and investing £100 of it back into more operating assets. If the business retains this “pay-out” profile of 67% (200/300), then it retains £5 of the £15 the new building block created this year generates. This £5 is invested in assets in a year’s time making a total investment of £105. With a 15% return this in turn means that the future building block generates just under £16 (15% of £105). Our future building block has a Net Present Value (NPV) of £52 and we have an annual growth rate in NPV of 5% (£52/£50).

How does the growth rate of our future building blocks impact our future value?

Part three of Our Valuation: the future recurring cash flow of £50, growing at 5% per annum is worth £1,000[3] (£50 / (10% – 5%))

So what is our business worth?

We have built a business out of basic building blocks and arrived at a value made up of two elements. A past value from existing cash flows of £3,000, and a future value of £1,000 from building blocks the business will create in the future.

In total our business is worth £4,000.

I want to take a step back and make the point that the valuation we have built is based purely on an assessment of the Return on Capital the business can achieve. This essentially is our building block. What we have not done, and which I am sure all of you are familiar with, is value the business by projecting out profit and cash flows extensively into the future, and then discounting these. We have valued this business based purely on an assessment of the RoC it can make. If this sounds disarmingly simple then I would say that it really crystalises an absolute fundamental concept when thinking about the value of a business: what are its strategic advantages and disadvantages and how to they impact the RoC it makes.

Why Return from Capital matters

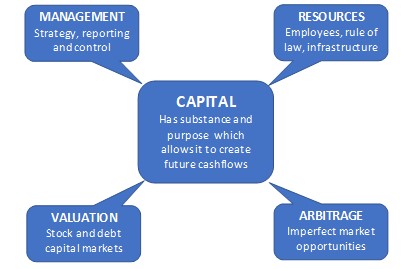

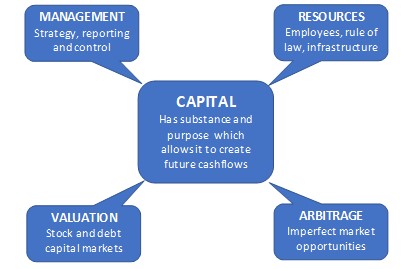

This is an opportune moment revisit the definition of capital I put forward in my article Capital: An Introduction from a Treasurer’s Perspective, summarised in Figure 4 below.

Figure four: four elements define capital

Capital, in the business world at least, needs four distinct elements to make it a tangible business asset. These elements all fall under the big umbrella heading of strategy. In fact RoC is the financial manifestation of a successful, or unsuccessful, strategy. This simple number tells us a very great deal about the strategic position of the business, something that a focus on profit simply does not. Some of the implications of this are listed below:

- Acquisition and disposal activity: looking at the historic RoC and that projected into the future for the target can give a real insight into the valuation and potential synergies, especially where the acquirer believes they can improve the RoC.

- Business Unit valuation within the firm: aiding internal portfolio management by comparing RoC achieved to a required target such as MWACC™. This in turn supports capital allocation decisions and target setting for performance management purposes.

- Investing decisions: a share price can be assessed against the RoC the firm reports to determine if there is potential under or over valuation in the price.

A final word

A focus on profitability potentially leaves a gaping hole in any assessment of value or performance. It can at best only be an indicator of whether value has been created. The Return on Capital approach described in this article however gives insight into the success of the strategy and where capital should be allocated to in order to create value. It is also surprisingly easy to determine and produces a simple and understandable single metric output. Assessing how this metric stacks up against the strategic position of the business is a key enhancement to the traditional valuation process.

References

[1] Capital Asset Pricing Model: Risk free rate + (β x Equity Risk Premium)

[2] Remember you value a stream of cash flow stretching into perpetuity by dividing them by the discount factor

[3] A growing stream of cash flows is valued by dividing the cash flow by the discount rate minus the growth rate